Michael James's Island of the Thieves masquerades as a sweeping historical epic while functioning as something more subversive: a darkly comic satire of how empires manufacture meaning from absurdity. Through the story of Eng Kang—a Chinese boy who becomes Juan Bautista de Vera in the Spanish colonial Philippines—James constructs a narrative that is part picaresque, part theological farce, and wholly committed to exposing the machinery of colonial mythmaking.

The novel's satirical edge announces itself early. Eng Kang, a twelve-year-old pirate captive, is sentenced to death twice before his thirteenth birthday. He escapes the garrote by spontaneously reciting the Gospel of John in Latin—not through divine intervention, but because he happens to have an eidetic memory and has been studying with a priest. The Spanish authorities, desperate for proof of their civilizing mission, immediately declare it a miracle. "The Miracle of Dilao" becomes official doctrine, and young Eng Kang is transformed into Juan Bautista de Vera, living evidence that God smiles upon Spanish conquest.

What might be triumphant in a conventional historical novel becomes, in James's hands, the setup for an extended joke about the performative nature of colonial power. Juan survives by becoming an idol—literally. As he later realizes, "He had become an idol. Like the calf, he was polished and veiled and gleaming. Empty." The boy saved from execution becomes a hollow vessel into which empire pours its own meaning.

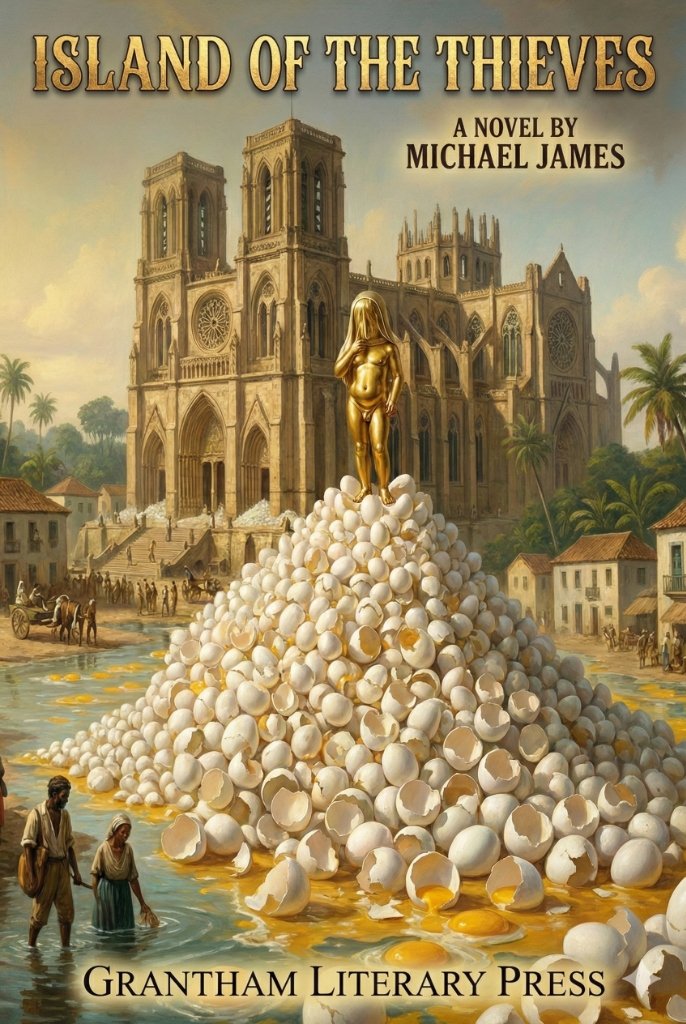

James's prose oscillates between deadpan observation and savage irony. His descriptions of the physical world are precise and often beautiful, but they serve to heighten the absurdity of what transpires within it. Consider the cathedral's construction, which runs throughout the narrative like a dark comedy of imperial overreach. To create the mortar, the Spanish need millions of egg whites. Soon "the mountain of eggshells rose jagged under the sun," and the entire colony drowns in unwanted yolks: "Meals became duties. Heavy. Predictable. The mere sight of golden custard, once a delight, now made stomachs turn."

The novel's structure mirrors its themes. We watch Juan build—fields, a factory, a fortune—only to see these constructions systematically dismantled by the same forces that elevated him. The cathedral rising in the background throughout the narrative becomes a powerful metaphor for the architecture of faith and empire: beautiful, enduring, and built on the backs of those it claims to save. James makes us feel the weight of this irony without belaboring it.

Where the novel excels is in its exploration of identity as performance. Juan is never simply one thing. He is Chinese by birth, Spanish by baptism, neither fully accepted nor entirely rejected. James captures the exhaustion of this liminal existence: "He had survived by performing faith. Worse. He had grown fluent in it." This is not a novel about a man finding himself, but about a man learning to navigate the impossibility of selfhood under colonial rule.

The relationship between Juan and Isa, a woman who refuses baptism and maintains her indigenous beliefs, provides the novel's emotional center. Their connection is rendered with subtlety—James resists melodrama even when addressing profound differences in worldview. When Isa sells Juan's fighting cocks to pay for a child's burial, the gesture speaks volumes about competing value systems: empire's transactional faith versus indigenous reciprocity.

The novel's ambitions occasionally exceed its grasp. The middle section, following Juan's expedition with the Jesuit Domingos in search of the Lost Tribes of Israel, loses narrative momentum. The burning of temples and forced conversions, however historically accurate, become numbing through repetition.

Yet these are minor flaws in a work of considerable ambition. Island of the Thieves succeeds because James understands that historical fiction at its best illuminates not just the past but the mechanisms of power that persist into the present. The novel's central question—"Whose story are you in?"—resonates beyond its colonial setting. In an age of contested narratives and historical revision, James reminds us that the power to shape memory is perhaps the most lasting form of domination.

The novel's ending is both tragic and quietly defiant. Juan's execution becomes, through rumor and doubt, the moment when empire's control over narrative begins to fracture. James writes: "Memory is a fragile thing. It frays at the edges. Resists control." In refusing to provide clear closure—was the head in the glass box really Juan's?—James enacts his own resistance to imperial certainty.

The novel arrives with a translator's note claiming to be a modern rendering of a 17th-century manuscript. This framing device, while potentially gimmicky, actually deepens the book's themes. If the entire text is a translation, then we are once removed from Juan's actual voice—a fitting commentary on how colonized subjects speak to us only through mediated channels.

Island of the Thieves is an impressive achievement that will reward readers willing to engage with its complexities. James has written a novel that is at once intimate and epic, a story of one life that illuminates the machinery of empire. It reminds us that history is not simply what happened, but what is remembered—and who gets to do the remembering.

In the end, Juan Bautista de Vera steps off the wall not in defeat but in defiance, choosing the manner of his ending even as empire chooses his end. It is a small victory, perhaps. But as James's novel demonstrates, sometimes the act of asserting one's own narrative, even in the face of certain death, is the most radical act of all.

This is a critical perspective that often gets overlooked. Excellent reporting.

I'm not sure I agree with the conclusion, but the historical context is helpful.